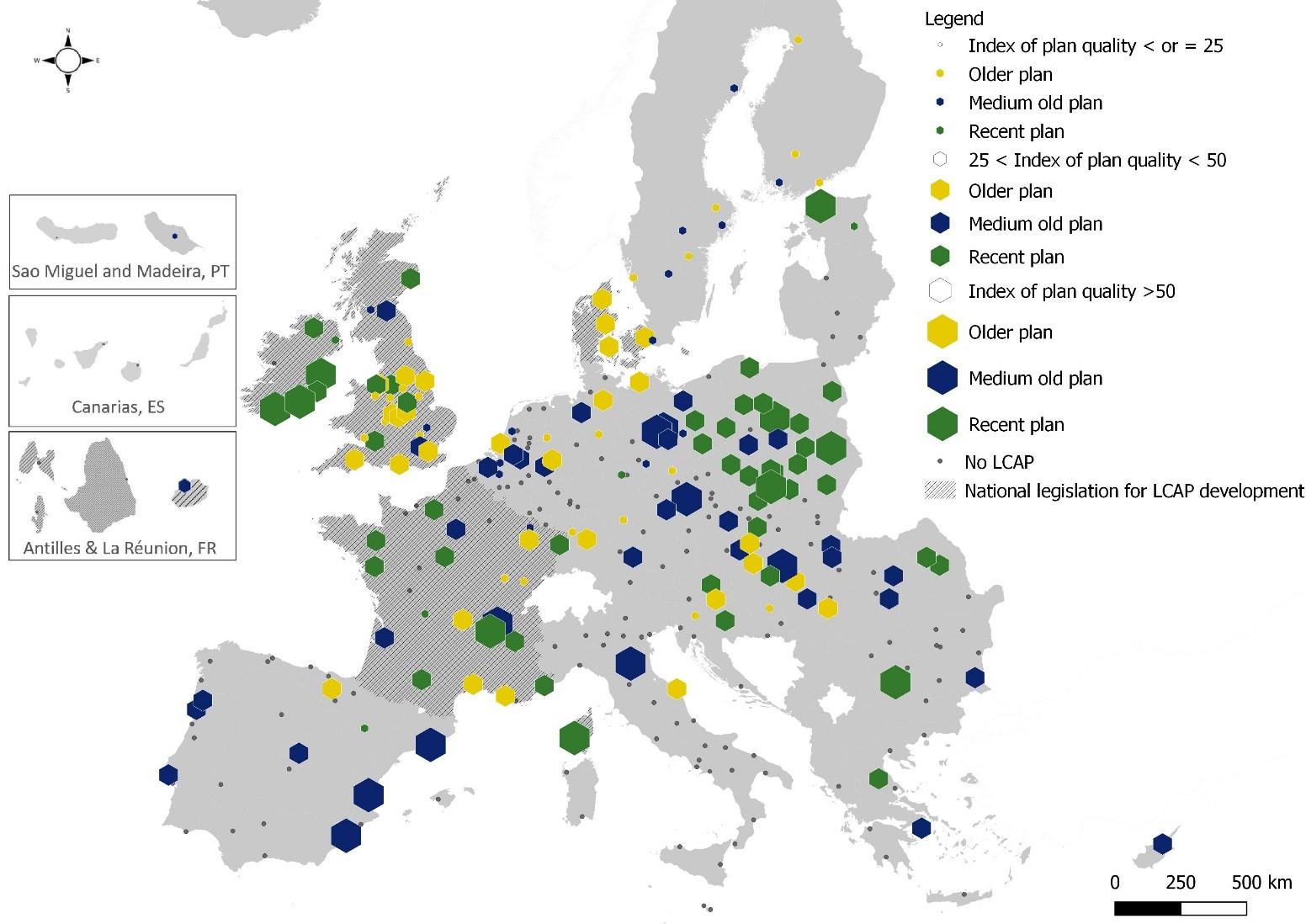

Fig. 1: Map of European cities with urban climate adaptation plans and their quality score. Colours refer to the age of the plan, i.e. the year of publication, with roughly equal cities in each age group (dividing the total of 167 cities with adaptation plan(s) by three). Yellow depicts plans that are published before mid-2015. Blue depicts plans that are published between mid-2015 and mid-2018. Green refers to plans that are published after mid-2018. Cities in our sample of 327 without an adaptation plan/ plans are shown by small grey dots. Shaded countries have national legislation that requires cities to develop urban climate adaptation plans (France, the UK, Ireland, and Denmark)

Urban adaptation plans in Europe are getting better over time: but we are not focussing on people most in need

A group of scientists evaluated urban adaptation plans in 167 European cities to understand if there is an evolution on plan quality over time. It was found that, from 2005 to 2020, overall adaptation plan quality has improved. When looking into different components of plan quality, we have found that cities’ adaptation planning mostly improved in setting adaptation goals, in suggesting thorough and varied adaptation measures, and in detailing out their implementation. On the other hand, there has been only a slight improvement on monitoring plan implementation and on including civil society in plan making. Likewise, newer plans are slightly better at proposing measures that match the previously identified climate risks. However, the involvement of vulnerable people and the monitoring of adaptation measures by those people affected is still rare. There is a clear positive trend in urban adaptation plans in Europe, but still a long way to go towards more inclusive and robust adaptation planning towards climate risk reduction.

Global temperature increases confirm that climate change is already happening. We therefore need to adapt to its impacts. Adaptation formed a key part of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which stressed the need to review progress on adaptation, including through regular “Global Stocktakes”. However, given that the effectiveness of many adaptation measures only really becomes apparent after some time, often only after a severe weather event such as a heatwave or storm has hit, it is notoriously difficult to assess this progress. Indeed, to date there is no agreement on the current state of adaptation, what ‘progress’ means, and how it could be assessed.

One approach involves examining the contents of adaptation plans, to analyse the extent to which they identify climate risks and propose measures to reduce the scale of potential impacts. In our new study, published in npj Nature Urban Sustainability, we develop and apply three different indices to assess the quality of these plans, and apply them to 167 cities across Europe.

We found that these cities have improved in their abilities to plan for adaptation. These improvements may come about through processes of collective learning, knowledge transfer, capacity building, transnational networks and other types of science-policy collaborations. However, most local governments are still not considering the needs of vulnerable people, nor involving them in policy formulation and monitoring—something that we regard as necessary for a good adaptation plan, in order to make sure adaptation works for people most in need of it.

Why is it important to evaluate the quality of local climate adaptation plans?

Climate threats are particularly pronounced in cities many of which are highly vulnerable to heatwaves, flash flooding, coastal erosion and storms. Therefore, we might expect that many city governments have set out how they seek to address these threats in official plans. These plans cannot tell the whole story in terms of actual progress in the collective reduction (or redistribution) of climate risks, because they do not tend to monitor implementation or the effectiveness of previous policies. However, they can provide information about the quality and relevance of adaptation processes and actions, and help to assess the likelihood that cities’ advance adaptation goals by reducing risks and increasing resilience equitably. As one previous study put it, ‘the best method to ensuring robust adaptation is to ensure rigorous adaptation planning processes’.

As such, developing and applying a set of indicators to measure and track the quality of urban adaptation plans can help us to learn collectively about how to deal with climate threats better. Our indicators have been incorporated into a free online tool to help city practitioners assess the quality of their own plans, and benchmark their progress against others.

Defining urban adaptation planning quality

We assessed adaptation plan quality according to six principles that are already well-established in previous studies: 1.) fact base of impacts and risks in the local area; 2.) adaptation goals; 3.) adaptation measures; 4.) details on the implementation of adaptation measures; 5.) monitoring & evaluation of adaptation measures; and 6.) societal participation in plan creation. In addition, we introduced a relatively new aspect concerning the “consistency” of the plans. Consistency means that impacts/ risks, goals, measures, monitoring, and participation are aligned with each other. For example, if a city identifies that it is vulnerable to heatwaves, which put older people are particular risk, then a good plan designs and implements specific heat-related measures that target older people, and puts mechanisms in place to assess whether their vulnerability to heat risks reduces after implementation. We argue that consistency is a very important aspect of plan quality.

Based on a combination of these six principles and various consistency measures, we developed a new index (named ADAQA) to assess plan quality, and applied it to urban adaptation plans in a sample of 327 European cities, published between 2005 and 2020.

Distribution of plan quality in European cities

Of the whole sample, about 50% , i.e. 167 cities, had an adaptation plan (Fig. 1). Most plans are found in the United Kingdom (UK) (30 plans), Poland and France (22 plans each), and Germany (19 plans). A total of 53 of these 167 cities (32%) developed it under a national, regional, or local law that requires municipalities (sometimes above a certain threshold of population size) to develop an urban climate adaptation plan. This was the case for cities in Denmark, Ireland, the UK and France.

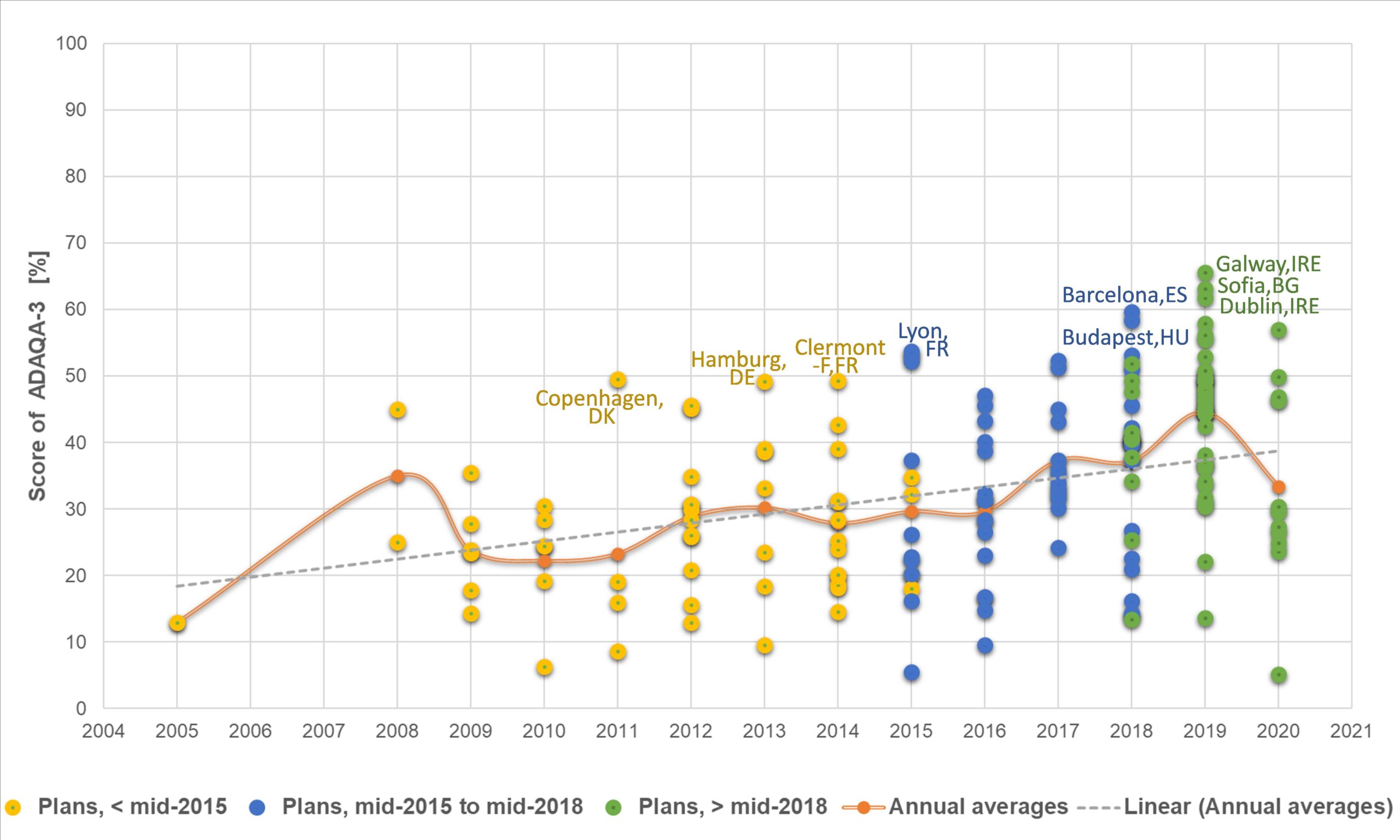

The cities of Sofia (BG), Galway (IE), and Dublin (IE) scored highest (Fig. 2) in the adaptation plan index. Notably, the Irish government requires cities to produce adaptation plans that included certain features (e.g. an assessment of climate risks to the urban area), and this contributed towards their high scores. Galway achieves the highest score and performs particularly well against Principles 1 (fact base: impacts), 4 (implementation), and 6 (participation), and also in terms of taking account of vulnerable sectors in its plan. The city set clear priorities for different actions, identified responsible parties, set out a timeline for implementation, and developed a detailed budget. Furthermore, it involved a wide range of stakeholders in the plan-making process.

Evolution of plan quality over time

We divided our cities into three temporal groups, depending on when their most recent plan was published. We found that plan quality significantly improved over time across these temporal groups (Fig. 1), and also on annual basis (see Fig. 2). Assuming linearity, plan quality increased by about 1.3 points per year from 2005 to 2020.

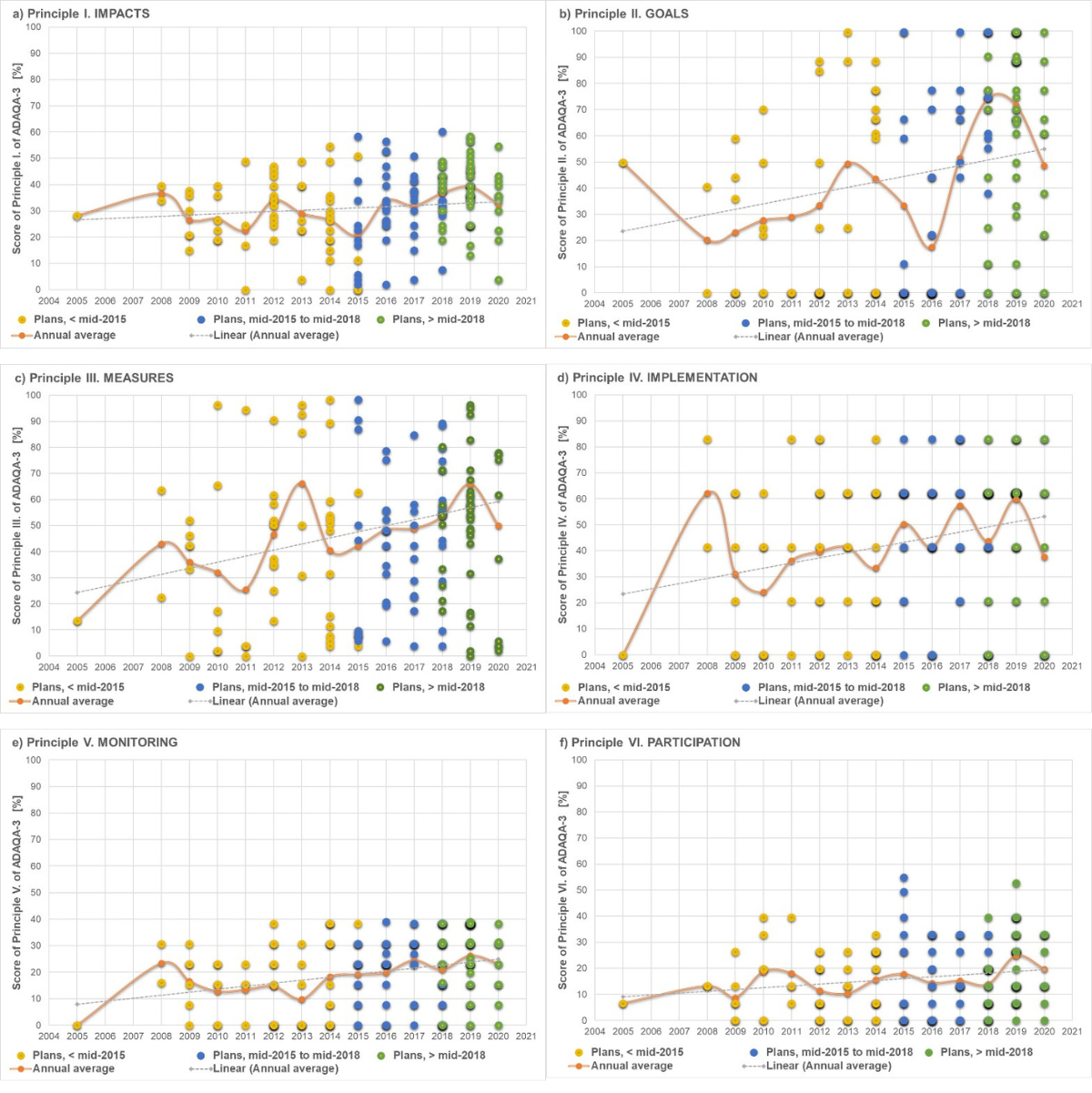

However, there are clear differences in terms of the various principles of plan quality (Fig. 3). On average, cities improved most in terms of goal setting, suggesting detailed and different measures, and setting out the implementation approach. The plans improved only slightly with regard to monitoring, e.g. the progress of implementing the measures, and including civil society in plan making, i.e. participation.

Fig. 2: Scores of the plan quality index ADAQA-3 per city over time. The scores are displayed per city and year in which the adaptation plan was published, plus averages of each year and linear trend line, 2005 to 2020. Each dot represents the plan/ plans in one city. The dot colours indicate the temporal group the adaptation plan belongs to, i.e. yellow: older (before mid-2015), blue: medium-old (mid-2015 to mid-2018) and green: recent plans (after mid-2018), with an almost equal number of plans in each group. We call out the first three cities with the highest adaptation plan quality score in each temporal group. The exact scores of each city for ADAQA-1/2/3 are provided as Supplementary Tab. 1 in our published paper

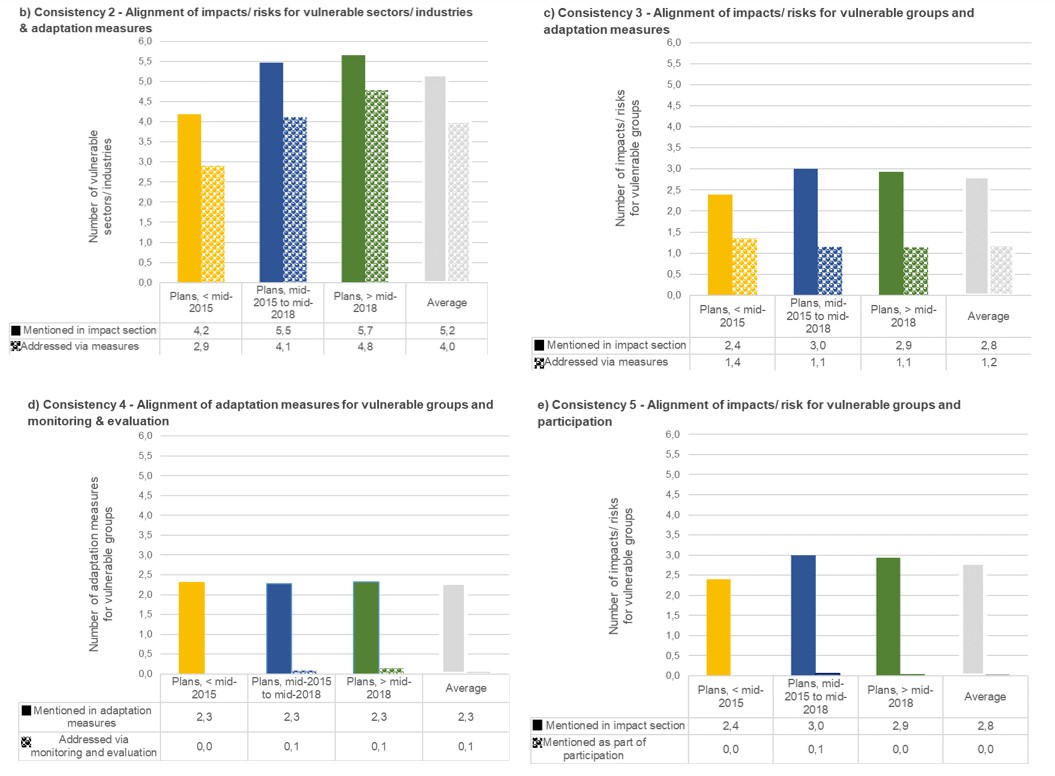

Consistency of plans over time

As mentioned, one of the central characteristics of our index is its focus on consistency between identified climate risks and the measures that the city plans and monitors. We find that the consistency improved slightly over time (Fig. 4), particularly with regards to aligning impacts/ risks with adaptation goals (not shown), and vulnerable sectors/ industries with adaptation measures (consistency 2 in Fig.4). The impacts/ risks for vulnerable groups and how these groups were involved in plan development (consistency 5), as well as how adaptation measures for vulnerable groups were monitoring over time (consistency 4), were also better aligned in later plans.

Very few plans engage vulnerable people in developing plans and monitoring measures, although their involvement in these processes has increased slightly over time. In other words, vulnerable groups (such as infants, older people and those on low incomes) are rarely involved in participation processes and the vast majority of plans make no mention of monitoring and evaluation to address their specific needs. Moreover, urban adaptation plans got worse over time in planning for measures that particularly address these vulnerable groups (consistency 3). That means, more recent plans involve less measures that particularly address identified vulnerable groups.

Fig. 3a-f: Scores of the adaptation plan quality principles (principles I. to VI.) in ADAQA-3 per city over time. Each dot represents the plan/ plans in one city. The dot colours indicate the temporal group the adaptation plan belongs to, i.e. yellow: older (prior mid-2015), blue: medium-old (mid-2015 to mid-2018) and green: recent plans (after mid-2018), with an almost equal number of plans in each group.

Overall, therefore, although the quality of urban adaptation plans in Europe has improved since 2005, many cities are still lagging behind or are yet to even produce a plan. Furthermore, most of the existing plans do not sufficiently take account of the specific needs of those people who are particularly vulnerable to climate impacts. We hope that our study and the free online tool can help practitioners and policymakers reflect on what they can include in future plans, and thereby contribute towards improved resilience in cities across Europe and elsewhere.

Figure 6: Scores of the consistency measures (consistency 2 to 5) in ADAQA per temporal group. The bar colours indicate the temporal group in which the adaptation plan was published, i.e. yellow: older (prior mid-2015), blue: medium-old (mid-2015 to mid-2018) and green: recent plans (after mid-2018), with equal plans in each group.

Reckien, D. et al. (2023) Assessing the quality of urban climate adaptation plans over time, npj Nature Urban Sustainability, doi:10.1038/s42949-023-00085-1

Recent Comments