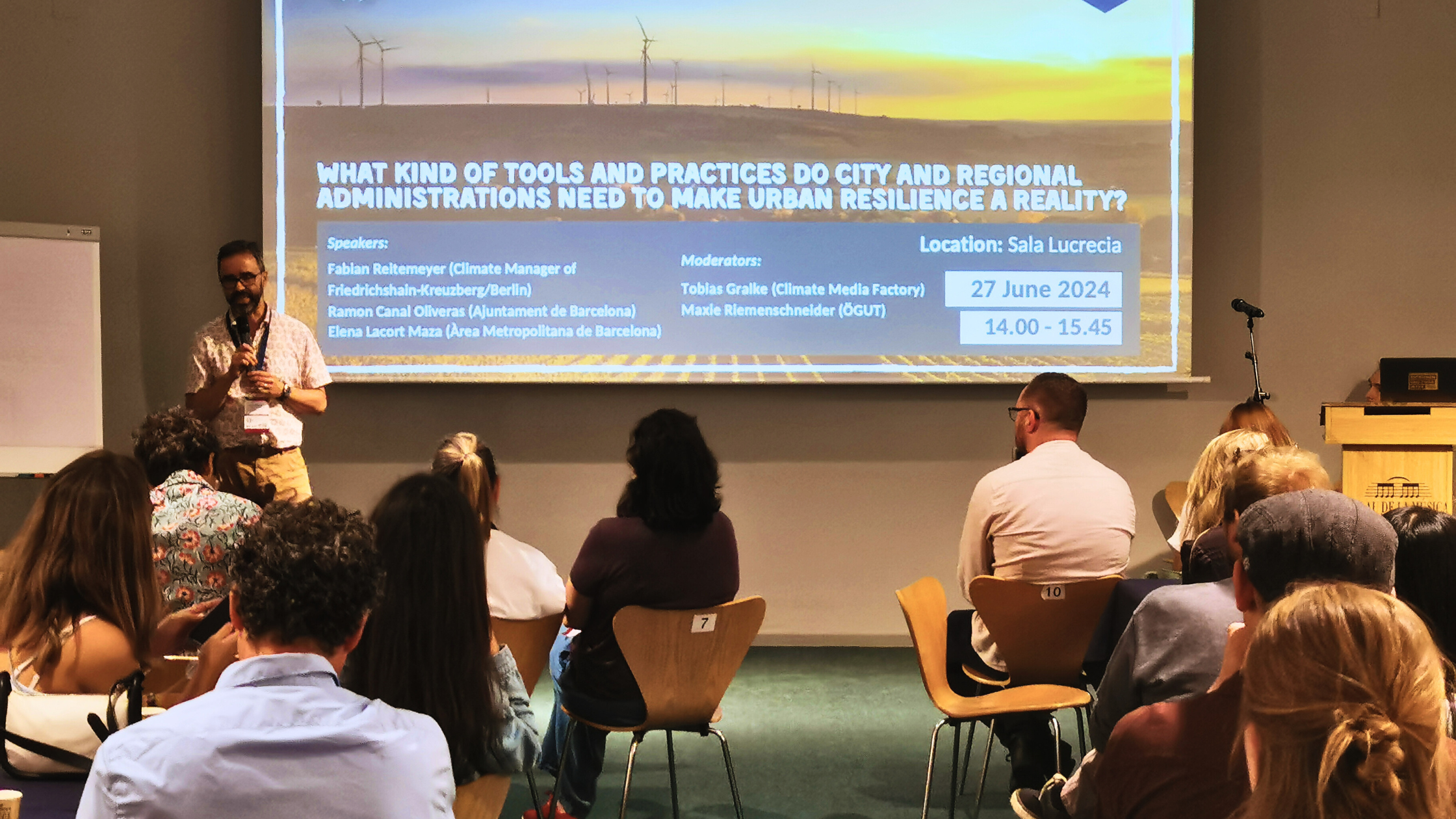

LOCALISED at EURESFO24: Advancing Urban Resilience in Small and Mid-Sized Cities

From June 25 to 27, LOCALISED was present at EURESFO24 and hosted a workshop titled “What Kind of Tools and Practices Do City and Regional Administrations Need to Make Urban Resilience a Reality?“. Our goal was to empower municipalities to develop effective, resource-efficient, and socially inclusive climate strategies through practical tools and collaborative discussions.

Workshop Overview

The workshop addressed the specific challenges faced by small and medium-sized cities and regions in developing climate action plans. With around 80 participants from diverse fields—including academia, policymaking, and the private sector—the discussion aimed to provide practical insights and strategies for making urban resilience a reality. Indeed, the variety of participants enabled us to collect a wide range of perspectives, by enriching the dialogue, and allowing for a more comprehensive exploration of the potential solutions in for mitigation and adaptation plans.

Key topics included:

- Developing Ambitious Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plans (SECAPs) with Limited Resources: How can smaller municipalities create climate action plans with constrained budgets?

- Integrating Mitigation and Adaptation Measures: What are the best practices for combining efforts to reduce emissions and adapt to climate impacts, while also considering the social implications of these measures?

- Aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): How can climate action plans be linked to broader SDGs to ensure comprehensive and synergistic development?

- Engaging Citizens Effectively: What strategies can help municipalities engage citizens as agents of change?

- Navigating Governance and Stakeholder Dynamics: How can cities and regions ensure collaboration across various governance levels, departments, and stakeholder groups?

Expert Contributions

We were honoured by the presence of distinguished speakers:

- Fabian Reitemeyer, Climate Change Officer at the District Office of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg

- Ramon Canal Oliveras, Director of the Technical Programming Office, Barcelona City Council

- Elena Lacort, Head of Climate Change and Air Quality Office, Barcelona Metropolitan Area

Their practical insights enriched the dialogue, offering valuable perspectives on overcoming common obstacles in climate action planning.

Showcasing LOCALISED Tools

The workshop featured demonstrations of two key tools developed by the LOCALISED project:

- The LOCALISED Climate Action Strategiser: Presented by Tobias Gralke, Project Developer & Researcher at Climate Media Factory, this tool automates the generation of tailored climate action measures for SECAPs. It enables municipalities to customise emissions reduction solutions to their specific needs and resources.

- The LOCALISED Citizen Engager: Maxie Riemenschneider, Scientific Manager at the Austrian Society for Environment and Technology, introduced this tool, which focuses on co-creating climate strategies with citizens. It facilitates the inclusion of public input in both overarching strategies and specific measures, fostering community involvement and support.

Feedback and Knowledge Exchange

After presenting the tools, participants from various countries and professional backgrounds joined different groups and provided invaluable feedback on the LOCALISED tools, but also exchanged their expertise on decarbonization pathways and best practices. Their inputs have been crucial for refining the tools to better meet the needs of cities and regions across Europe and increase our knowledge.

Marketplace Engagement

In addition to the workshop, LOCALISED was also present at the marketplace and many visitors explored our initiatives, tools, activities, and outcomes. The booth also served as a platform for gathering interest from participants eager to engage in the co-design and testing of our tools.

LOCALISED participation at EURESFO24 underscored our commitment to supporting small and mid-sized cities in their climate action efforts. For more information about our tools, please visit the website here.

The participation of LOCALISED in EURESFO24 has been made possible thanks to the collaboration of the following people: Christiane Walter from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Jordi Pascual, Nadia Soledad Ibañez Iralde and Enric Mont Lecocq from IREC – Catalonia Institute for Energy Research, Maxie Riemenschneider from ÖGUT – Austrian Society for Environment and Technology, Sara Dorato and Katja Firus from T6 Ecosystems srl and Tobias Gralke and Bernd Hezel from Climate Media Factory.

Recent Comments